A tradition that needs to be revived

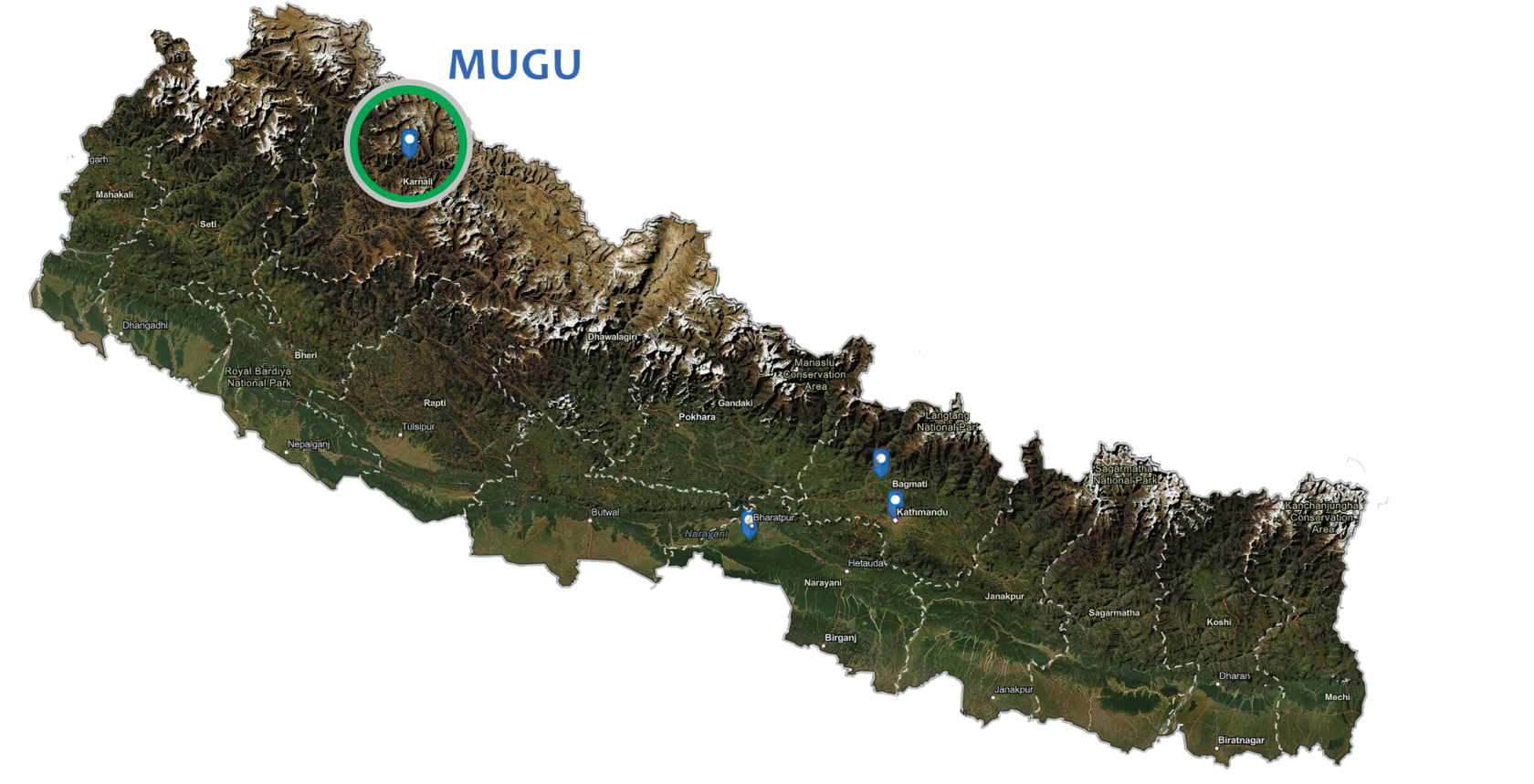

Our project region Mugu consists of two regions named after the indigenous people: the upper Jadan and the lower Khasan. The Jad are Tibetan lamas, the people of the southern Khas region, who came from northwest India. Both brought important knowledge with them: the Khas had agricultural experience and had metal weapons, the Jadan people were sheep farmers. The combination of both formed a good basis for securing livelihoods in the region.

WE ARE INEXPECTIVELY LINKED TO YOU. “

THE SHEEP AS THE BASIS FOR ACTION | To make it worthwhile, a family kept at least a few dozen sheep, some more than 100. The sheep can carry 10 to 20 kg, making it the perfect means of transport and the basis for the well-organized trade of the Mugali. In the summer the men moved to the border or to Tibet in caravans of sheep. The sheep carried rice, which was exchanged in Tibet for the much cheaper rock salt there. At the beginning of winter they moved on as a whole caravan of sheep to warmer areas. Here they got more rice for less salt, because there was plenty of rice in the river valleys and the people there urgently needed salt. In exchange for the sheep’s manure, the farmers in the south gave them a place in the harvested fields. They made their camps, let the animals graze, the men sheared sheep or worked as lumberjacks, the women wove carpets and blankets. They sold these products right there and earned what they needed to live with the earnings. The children grazed the sheep and played with the trained Tibetan herding dog that accompanied each caravan of sheep.

This seasonal migration took place in the same places every year. An economic transaction turned into a social one, giving a new meaning to the exchange between peoples of two different religions and cultures, which was passed on from generation to generation.

THE FLIES ARE COMING, THE SHEEP HAVE TO GO | The flourishing trade came to an end in the early 2000s. The government had built an airstrip in Mugu and from 2003 airplanes and helicopters brought more and more rice, salt and other goods. The government set up the Rara National Park and declared a large part of Mugu a nature reserve – the sheep were no longer allowed to graze in the protection zones. In addition, a forest protection program was initiated in Nepal in the 1980s. The municipalities forbade cattle and sheep farmers to let animals graze in the forest. As a result, the shepherds lost their usual rights to grazing land. Today the farmers only keep a few sheep, the shepherds migrate to the high mountains in spring and bring the well-fed sheep to the market in autumn.

SHEEP ARE AND PROMOTE TRADITION | The older generation still likes to use local wool products. Sipu Rokaya, 56, from Jiuka Village said, “Every summer I shear my sheep to make carpets, blankets, pants, coats, and sweaters. We cannot imagine life without sheep. We are inextricably linked with them. The sheep always brought us salt and rice, they gave us clothes and meat for celebrations. “

As we move through the villages in Mugu, we see that almost every household has sheep. Most of all, we see men spinning wool, even when they are walking, talking, or holding meetings. The traditional houses wear a pair of sheep horns on the top of the door. “It’s been a tradition ever since. Our civilization started with sheep and this is still going on, “explained Sipu Rokaya. Every year when the Mugali sheep sacrifice, they place the skull with horns on the door frame. This way, no evil spirit can enter your house.

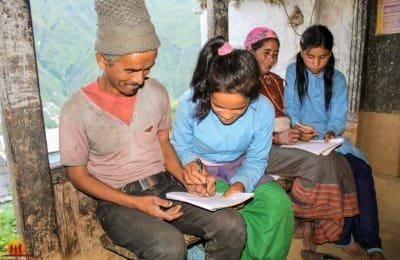

Reconsideration and a new beginning | The elders in Mugu take pride in their culture. They don’t want any dependency, they keep their identity and dignity. But the passage of time and new developments threaten sheep culture. Until recently, sheep from the region provided woolen clothing and meat to the entire western region of Nepal. Now the same sheep farmers are street vendors selling clothes from China. The same people travel across the border, bringing thousands of sheep from Tibet to sell during the Dashain festival. It is high time to change agriculture and strengthen the local culture.

Back to Life therefore supports the farmers in growing fruit trees. The fertilizer for the plantations comes from the sheep. The grass under the trees can in turn be fed to the sheep. This is a contribution to the restoration of the Mugu ecosystem.

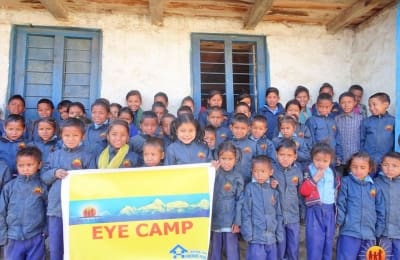

And something else good: By eliminating the shepherds’ long winter hikes, the children can now go to school permanently.